Prefatia

The topic is “primary sources” — the real deal — documenting the lives of these two poets. First fact:

lots for Chaucer; little for Shakespeare. Bottomline: neither set of records is conclusive about the

essentials of who these people were as poets or personalities — as people think they know other

people “pretty well,“ or even by clinical “presentation.”

But this apparent ignorance has never stopped record-keepers from drawing unsupported

conclusions. Here is an example within an example:

This 19th Century reader of Life-records of Chaucer acts (righteously?) to correct the book editor’s

facts about the color of Shakespeare’s eyes!

But not all scholars and readers are humorless know-it-alls. Some realize the reflexive response of

human readers — to think we know writers by what they write — is a wrongheaded idea when

studying poets and people. Some scholars even have fun in being so presumptuous as to make a go

at these two:

Time will tell which of us ends up as a Dogberry, the Barney Fife of Messina.

Exempla Paria

I

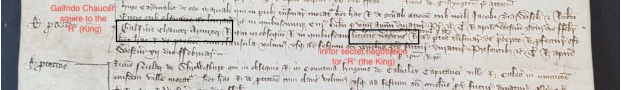

Chaucer King’s Soldier: Payment of a ransom in Spring 1360

In his late teens, Chaucer was captured near Rheims. Edward III and others put up the money.

Chaucer’s name, I gesse, is at the end of the fourth and beginning of the fifth lines.

Shakespeare young(er) husband and father: birth and death

Tales are handed down through 18th-century biographers that Shakespeare was nabbed for poaching

when a youth. For certain, though, there exists a public record of a christening of twins, a brother and

a sister to 19-month-old Susanna Shakespeare, also a church-documented Stratford Christian.

Judith outlived her father. Hamnet died at age 11. What of the names? In Stratford, 20-year-old Will

and 28ish Anne Shakespeare were neighbors to Hamnet and Judith Sadler, who — three years later

— named their son William. The rest is silence.

II

Chaucer as King’s ambassador: A letter of protection

Here is a 1377 letter of protection for Chaucer on the king’s ‘secret business’ (secretis negociis

R[egis]) as he and others attempt to negotiate peace treaties between England and France less than

half way through The Hundred Years’ War.

First in Rheims, then as on this on business to the continent, records of events confirm the impression

from his work that Chaucer knew Latin (from school) along with learning French and Italian in

preparation for and during his European travels.

Shakespeare an up and comer: A King’s Man

Meanwhile — so to speak — in 1602 at 38, Shakespeare had built his share in the Lord

Chamberlain's Men to 12.5 percent. At age 39, he lucked out. On May 3, 1603 , James I arrived in London. On May 18, Shakespeare, Burbage & Co., although they had performed often at court during

Elizabeth’s reign, began to emerge as “The King’s Men”, earning the privy seal of the new King. And

so a provincial glover’s son becomes acknowledged in court records by a King. Barring the plague (a

persistent threat to the health of both Chaucer and Shakespeare), the company were warranted by

the crown to perform anywhere in England.

This was not a small favor or pecuniary achievement. Consider that when James took the throne “over

a third of London’s adult population were viewing a play every month.”

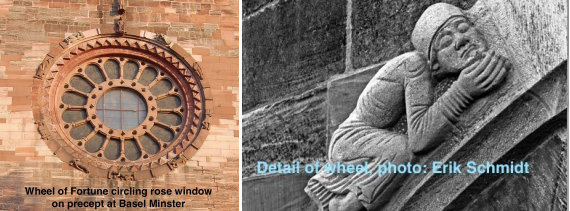

Chaucer on Fortune’s Wheel: Money promised, unpaid, resulting debt

Son of a London vintner, Chaucer started out as of a page for the Countess of Ulster, daughter-in-law

of Edward III. Later, in the court of Edward III, and when young Richard II first took the throne, he was “connected’; then — as a new posse gained hormonal Richards’s favor — not so much.

A first unfortunate turn of Fortune’s wheel: Chaucer is robbed two or three times outside of London in

1390 while traveling on official business, The robberies may be incidental, but pecuniary problems were unstinting when dependent on court disbursements. A search of Chaucer Society Life Records shows how difficult it was to collect monies from the government and patrons. (A search for arrears

returns most often the crown or patrons in arrears on promises to pay Chaucer and others.”

John of Gaunt (father of Henry IV) was a steadfast supporter but his influence declined until Richard

II’s “tyranny” (purge) of 1399. Here’s a record from 1395 in relatively good times, showing a gift of a

"goun de scarlet" [?] "Galfrid[o] Chaucer":

But as the crown’s fiscal efficiency faltered, so did Chaucer’s ability to pay his debts. In fact an

unenforced warrant for his detention for debt was issued in May,1398, a year before his death. How serious (or seriously taken) these debts of crown and court were in Chaucer’s life? We don’t know.

There was no Equifax.

Will’s Will: What to make of a second best bed

Wills are full of oddities. Here is Sheet 3 of the signed and attested will of William Shakespeare,

completed in final form on March 25, 1616, less than a month before his death. In his signature, a

wavering hand seems apparent. With a gatehouse apartment in London and a large house and family

in Stratford, he had earned the title gentleman (“gent.” in the document.) Here is the seemingly last

minute notation about what the poet gives to his wife.

The blue-boxed scribble squeezed between the line above ending with “William” and the line below

beginning with nearish “Shakspeare” is the only mention of a bequest to wife Anne, who would live until 1621, age 65ish. Speculation on what this part of Shakespeare’s will might indicate is endless.

It’s fun to guess but impossible to know what’s going on here!

Finis

What is curious still: these seeming lifeless documents stir in me fundamental questions these poets’

works evoked 45 years ago. Can anyone know who another person is? (e.g., what does a reader

know of the Pardoner, really?) And, in the case of King Lear, “who can tell me who I am?” — and will

be?

1 Screen capture from” FOREWARDS” §2, p.vi, Volume II of the four-volume 1875-76 Life-records of Chaucer, editor P. J. Puenivall, “Founder and Director of the Chaucer Society etc.” Ostensible topic: the coincidental seven-year gap in the found documents naming each author.

https://archive.org/details/liferecordsofcha02londuoft

2 Screen capture from Chaucer’s Mind and Art, a festschrift edited by A.C. Cawley; published by Oliver and Boyd, London and Edinburgh: 1969, pp. 166-190. Dogberry is an officious, bumbling nightwatch in Much Ado About Nothing.

3 Roger, Euan. “The civil servant’s tale: Geoffrey Chaucer in the archives.” National Archives [GB]., 30 October 2017. http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/civil-servants-tale-geoffrey-chaucer-archives/. [Image annotated] Subnote: Dr. Alan Baragona originated this research; all manuscript images of Chaucer source materials are taken from this excellent blog. Thank you Alan!

4 Schoenbaum, Samuel. William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life. Oxford Univ. Press, 1987, p. 94.

5 Blog: “The civil servant’s tale.” [Image annotated]

6 Schoenbaum, p. 211.

7 Alies, Adrian. “Paying for the privilege: a new Shakespeare discovery,” National Archives [GB], 23 April

[Shakespeare’s given birthday!] 2016. http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/paying-privilege-new-shakespeare-discovery/

8 In the binding of a volume containing “THE STORIE of Thebes” a poem John Ludgate; British Library,

Archives and Manuscripts: http://bit.ly/2hCDgWa

9 Life-records of Chaucer, editor P. J. Puenivall, et al. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1900

10 Again a special thanks to Dr. Alan Baragona for the gloss and the screen capture of this record from the Roger blog. [Image annotated]

11 “Life of Chaucer” in preface to The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Walter W. Skeat Oxford, Clarendon Press,1899, p. xliv.

12 From the online collection Shakespeare Documented, http://www.shakespearedocumented.org/; to see this part of Sheet 3: http://bit.ly/2jEOxcD

13 From Ellesmere manuscript in Huntington Library, http://www.english.upenn.edu/~jhsy/scholarship.htm

14 Shakespeare Documented, title page of 1623 First Folio, the first “collection” of Shakespeare's plays.

Comments